By James Heinz

She was born on the Lakes and died on the sea, but not before revolutionizing the rescue of those sunk at sea and participating in an immortal wartime incident.

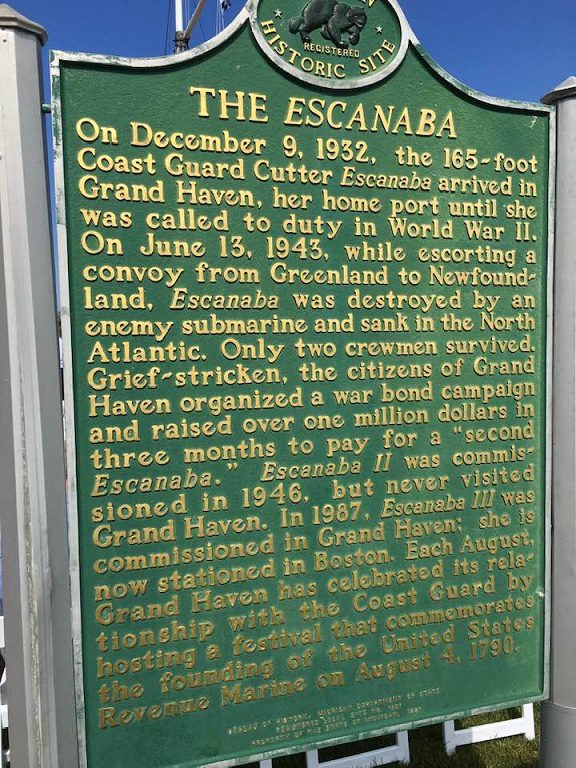

According to WMHS files, the first U.S. Coast Guard cutter named ESCANABA WPG-77 was launched November 10, 1932, at the Defoe Shipbuilding Yard at Bay City, Michigan. She was commissioned November 23, 1932. ESCANABA was the first of six “A” class cutters. They were designed to perform ice breaking, rescue, and law enforcement duties.

ESCANABA was 165 feet long and 36 feet wide and drew 12 feet of water. She displaced 1,005 tons. She had a crew of 105, was built of steel and powered by two steam boilers. She was the first cutter designed with a geared turbine drive, which worked well and gave her a speed of 15 mph and a range of 5,000 miles.

She was assigned to duties on the Great Lakes, where she was home ported in Grand Haven, Michigan. Grand Haven adopted the ship as their hometown ship and the community became very fond of the ESCANABA and her crew.

One of her more notable rescues was that of the whaleback steamer HENRY CORT. The CORT had already sunk three times in its career by the time of its final stranding on November 30, 1934. The CORT had left Holland, Mich., earlier that day on her way to Chicago. She encountered weather so bad that when she got a short distance from Chicago, a huge wave actually turned her around and pointed the ship back towards Michigan.

Captain Charles Cox of the CORT decided to surrender to the power of the storm and run before the raging sea, hoping to find safe haven along the Michigan shoreline. Just before 10 pm the CORT found herself just off the harbor at Muskegon. Captain Cox sailed her into the gap between the two sections of Muskegon breakwater, hoping to find refuge.

Just when he thought the CORT safe, an enormous wave hit the ship on her right side and pushed her left side onto the rip rap rocks on the north breakwater segment. The rocks punched through her bottom, impaling her on them.

The further actions of the waves on the CORT caused her to swing around the pivot that the rocks impaling her provided so that for the second time that day the ship spun around and she was now pointing back out towards Lake Michigan. The rocks ripped her bottom out and she settled onto them with a list to starboard, leaning up against the breakwater wall.

HENRY CORT Great Lakes Marine Collection of the Milwaukee Public Library and Wisconsin Marine Historical Society

The Muskegon Coast Guard station launched its 36 foot lifeboat with a 40 hp engine. They were no match for the storm, which simply swept the boat away until it was washed ashore several miles away, losing a crewman whose body was never recovered.

The next day the Muskegon Coast Guardsmen roped themselves together like mountain climbers and walked out on the wave swept breakwater and were able to bring the crew of the CORT ashore safely.

Throughout the night, the ESCANABA remained on station out in the storm tossed lake, comforting the crew of the CORT that they had not been forgotten. Pieces of the CORT can still be seen lying against the north Muskegon breakwater.

Like so much else, the outbreak of World War II changed the life of the ESCANABA. Her home base was changed to Boston, Mass., and she was assigned to the Greenland Patrol.

The ESCANABA opening a channel April 10, 1937 – Milwaukee Public Library and Wisconsin Marine Historical Society

In the words of Wikipedia, “The Greenland Patrol was a United States Coast Guard operation during World War II. The patrol was formed to support the U.S. Army building aerodrome facilities in Greenland and to defend Greenland. The patrol escorted Allied shipping to and from Greenland, built navigation and communication facilities, and provided rescue and weather ship services in the area from 1941 through 1945.” For the Greenland Patrol, the weather was the primary enemy.

The ESCANABA had been unarmed during her Great Lakes service. She was now armed with two 3 inch/76mm guns, two 20 mm guns, and a total of eight anti-submarine depth charge launchers.

The depth charge launchers may have giver her and those ships she escorted a false set of security. As the book “Guardians of the Sea” tells it, “Even the fastest were considerably slower than surfaced U-boats, none was equipped with radar until 1943… (and) their officers and men were inadequately trained in anti-submarine warfare.”

The cutters’ main function became to act as rescue ships, which was difficult because in the long Greenland winter, the rescues had to be done at night in rough seas. In addition, their crews knew that any ship that slowed or stopped to pick up survivors made itself more vulnerable to U-boats.

ESCANABA had a busy day on June 15, 1942. On that day she attacked two submarine sonar contacts and rescued 20 men from the freighter SS CHEROKEE, which had been sunk by a U-Boat.

During the rescue of the CHEROKEE survivors, it was found that cold water induced hypothermia sapped the victims’ strength so that they could not grasp ropes thrown to them or haul themselves up the side of rescue ships. To try to save them, ESCANABA’s Lt. Robert Prause dangled himself over the side of the ship while crew members held his legs so that Prause could grab the frozen survivors with his own hands.

But the ESCANABA’s date with immortality was yet to come.

On February 3, 1943, ESCANABA and two other cutters were escorting convoy SG-19. One of the ships was the civilian freighter DORCHESTER, which was a civilian steamer pressed into wartime service. She was carrying 904 Army troops, including four Army chaplains.

At 12:55 am off Cape Farewell, the DORCHESTER was struck by torpedoes from the German submarine U-223. The ship assumed a list to starboard, so some port side lifeboats could not be used, and other lifeboats capsized. The electrical system was knocked out, plunging the ship into darkness and preventing a radio distress message from being sent. The ship lost steam power so whistle signals could not be sent, and no distress flares were launched. The rest of the convoy did not know the ship was sinking.

The ships civilian captain had ordered the troops to sleep in their clothes with their life jackets on, but many soldiers had ignored this advice. Panic broke out as men trapped below decks in the dark tried to escape the sinking ship. Many of the passengers could not find their life jackets in the confusion.

Until the four Army chaplains helped them.

They were Lt. George Fox (Methodist), Lt. Alexander Goode (Jewish), Lt. Clark Poling (Baptist), and Lt. John Washington (Catholic). Their names were once immortal to the Greatest Generation, but have now long been forgotten. All four of them would give their lives to fulfill the commandment common to their faiths: Greater love than this hath no man, who shall lay down his life for his fellow man.

According to Wikipedia: “The chaplains sought to calm the men and organize an orderly evacuation of the ship, and helped guide wounded men to safety. As life jackets were passed out to the men, the supply ran out before each man had one. The chaplains removed their own life jackets and gave them to others. They helped as many men as they could into lifeboats, and then linked arms and, saying prayers and singing hymns, went down with the ship. According to some reports, survivors could hear different languages mixed in the prayers of the chaplains, including Jewish prayers in Hebrew and Catholic prayers in Latin.”

FOUR ON BOARD courtesy of Wikipedia

One survivor said, “As I swam away from the ship, I looked back. The flares had lighted everything. The bow came up high and she slid under. The last thing I saw, the Four Chaplains were up there praying for the safety of the men. They had done everything they could. I did not see them again. They themselves did not have a chance without their life jackets.”

The Four Chaplains went down with the ship. But for the men who had escaped the sinking DORCHESTER, the struggle for survival was just beginning. The water temperature was 34 degrees and the air temperature was 36 degrees. The men in the water began to rapidly freeze to death.

Until the ESCANABA arrived.

ESCANABA executive office Lt. Robert Prause had learned from his experience with rescuing the CHEROKEE survivors. Diving off a pier in Greenland, he had experimented using a rubber survival suit designed to be worn by aviators who went down in the ocean. He attached a parachute harness to the suit and a rope from the ship to the harness so that a man wearing the suit could jump into the sea and rescue sinking survivors too cold to respond.

The ESCANABA would now pioneer for the first time the use of rescue swimmers using survival suits to swim to those floating in the water but unable to rescue themselves. Three ESCANABA crew members jumped into the freezing water wearing the new, experimental suits: Ensign Richard A. Arrighi, Ship’s Cook 2nd Class Forrest O. Rednour, and Steward’s Mate 3rd Class Warren T. Deyampert. They rescued 133 people from the sea, only one of whom died later.

According to Wikipedia: “By way of the lines the rescue swimmers tied around those who were having trouble helping themselves, many struggling survivors who–debilitated by the cold–would have otherwise died, were hauled aboard the Escanaba by crewmen on deck.

Even those in the water who appeared to be dead were harnessed by the retrieval swimmers and pulled aboard – it was found that only 12 of the 50 apparently dead victims thus brought aboard by the retrieval teams actually turned out to be dead. The rest proved themselves to be quite alive once given the benefit of warmth, dryness, and medical attention”

In total 675 of the 904 people aboard the DORCHESTER died. It was the worst loss of American life from any American convoy in World War II.

The innovative rescue method so pleased the Navy that ESCANABA CO Carl Peterson received the Legion of Merit. Lt. Prause and ship’s doctor Ralph Nix received letters of commendation. Prause, and rescue swimmers Arrighi, Rednour, and Deyampert all received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, which is the Navy’s highest award for bravery in a non-combat situation.

All of these awards were awarded posthumously.

On June 10, 1943, at 5:10 am the ESCANABA simply exploded. Other ships saw a huge blast of flame and smoke shoot up from the ship, although no one heard any sound. She sank in three minutes. Only three survivors, including Lt. Prause, were recovered. Prause, who had rescued so many others, could not himself be rescued. He died aboard the rescue ship and was buried at sea. The other two survivors survived because their wet clothing froze to pieces of floating debris, keeping their bodies out of the water.

The cause of the explosion was never determined. One of the survivors reported hearing one of the ship’s .50 caliber machine guns firing just before the explosion. At first it was assumed that the ESCANABA had been sunk by a U-boat torpedo. But no U-boat claimed to have done so, so the Navy believed that the ESCANABA had been sunk by a drifting mine.

Thirteen officers and 92 men died aboard the ESCANABA.

The loss of the ESCANABA and its crew not only deeply affected their families, it deeply affected the citizens of Grand Haven, Michigan, the ship’s original home port. But, there was a war on, and the citizens of Grand Haven pitched in and bought $1.2 million in war bonds to fund a replacement for the original ESCANABA.

The second ESCANABA WHEC-64 was built in California and commissioned March 20, 1946. The second ESCANABA served in both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans until she was scrapped in 1974. She never entered the Great Lakes.

And then, in 1987, the Coast Guard cutter ESCANABA returned to Grand Haven.

No, it was not a ghost ship risen from the depths. This was the third ESCANABA WPG-77, a Famous class cutter. She was built and launched in 1987 in a Rhode Island shipyard, but returned to her namesake’s home port to be formally commissioned on August 29, 1987, before returning to the sea.

WMHS files show that 23 people who had seen the original ESCANABA and participated in the bond drive for her successor were invited to the commissioning. Ann McNeil, who was 13 when the first ESCANABA sank, remembered walking past the ship when it was based in Grand Haven. She saved her babysitting and blueberry picking money to buy a $25 bond to fund the second ESCANABA.

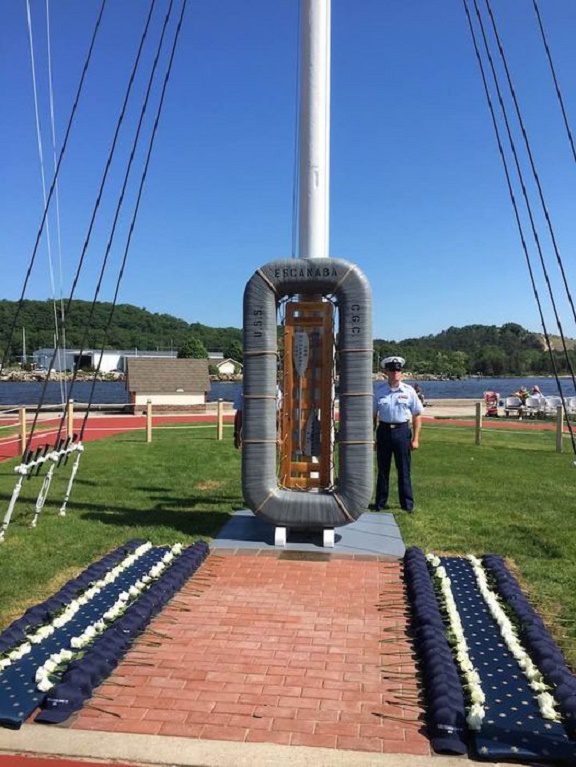

Escanaba Memorial Park – courtesy of their Facebook page

Today, Grand Haven describes itself as “Coast Guard City USA”. It is home to a Coast Guard station, and every year since 1924 the city has hosted Coast Guard Festival, which this year will take place from July 26 -29. During this festival there will be a memorial service for the original ESCANABA. The first ESCANABA is also remembered in Escanaba Memorial Park in Grand Haven, dedicated in 1949.

PAINTING OF FOUR courtesy of Wikipedia

The Four Chaplains were each awarded the Four Chaplains Medal by a unanimous special act of Congress in 1960. This medal was intended to have the same stature as the Congressional Medal of Honor. The text of the statute passed by Congress is below.

MEDAL courtesy of Wikipedia

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the President is authorized to award posthumously appropriate medals and certificates to Chaplain George L. Fox of Gilman, Vermont; Chaplain Alexander D. Goode of Washington, District of Columbia; Chaplain Clark V. Poling of Schenectady, New York; and Chaplain John P. Washington of Arlington, New Jersey, in recognition of the extraordinary heroism displayed by them when they sacrificed their lives in the sinking of the troop transport Dorchester in the North Atlantic in 1943 by giving up their life preservers to other men aboard such transport. The medals and certificates authorized by this Act shall be in such form and of such design as shall be prescribed by the President, and shall be awarded to such representatives of the aforementioned chaplains as the President may designate.

____________________________________

James Heinz is the Wisconsin Marine Historical Society’s acquisitions director. He became interested in maritime history as a kid watching Jacques Cousteau’s adventures on TV. He was a Great Lakes wreck diver until three episodes of the bends forced him to retire from diving. He was a University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee police officer for thirty years. He regularly flies either a Cessna 152 or 172.

This story was originally posted on June 13, 2024