On this day June 29, 1864, the two masted schooner ALVIN CLARK capsized off Chambers Island, Wis., during a severe gale with thunder, lightning, rain and hail. She took Capt. Dubbin and mate John Dunn, both of Racine, with her.

The CLARK was built at Truago, Mich., (now Trenton) in 1846 to carry salt from Buffalo and Oswego. She measured 105 feet in length. In 1853 the Milwaukee Sentinel noted she brought 1400 barrels of white fish, trout and pickerel from Twin Rivers and Whitefish Bay to Detroit. Besides fish she was known to carry whiskey, lumber, wheat and flour.

In 1967, Frank Hoffman was hired by local fishermen to dive and free their nets that had become snagged on something in Green Bay. Hoffman found the nets to be tangled in the mast of an old ship. That ship was the ALVIN CLARK and she was in excellent condition. Hoffman received the salvage rights and started bringing up artifacts and planning to raise the ship. This is an interesting story as it had never been done before. You might want to read more about it on your own.

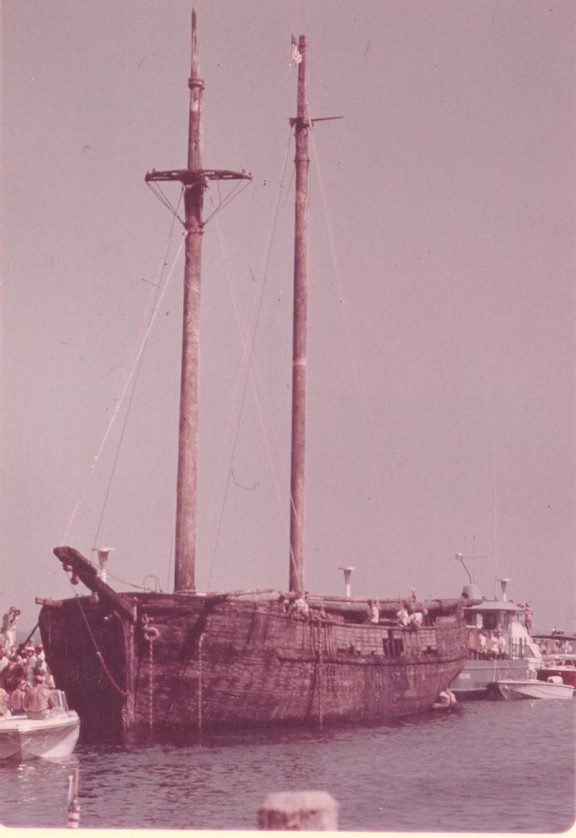

On July 29, 1969, the ALVIN CLARK was raised by Hoffman and his team. She was docked at Menominee, Mich., and opened as a museum with all her historic tools and artifacts. Unfortunately, weather and the elements were not kind to the CLARK and a fire did not help. She was later demolished in May 1994 and became landfill.

But, the great adventure of bringing up a schooner that had been underwater for 100 years molded a new generation of divers and historians. Our Shipwreck Ambassador Cal Kothrade was one of those. The following is his story of the impact the ALVIN CLARK had on him.

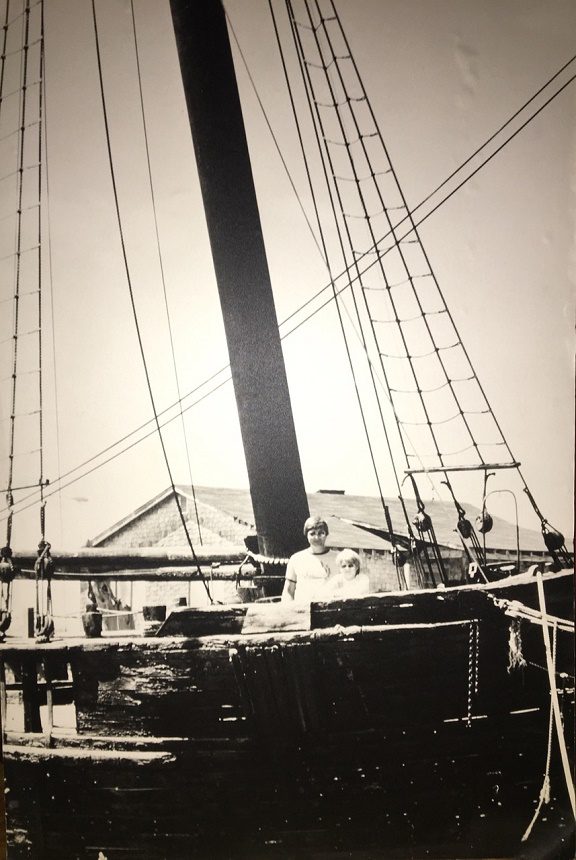

Cal Kothrade and his dad on the deck of the ALVIN CLARK.

A child’s memories of his first pirate ship – the ALVIN CLARK

by Cal Kothrade

I’ve been fortunate to fall into this niche I call ‘shipwreck photographer’. I’ve seen well over one hundred shipwrecks under the water from the west coast of California up to the nutrient waters of British Columbia, Canada. From the Graveyard of the Atlantic off Cape Hatteras, to the sunlit wrecks of the Florida Keys. From drug running cargo ships off Venezuela to USCG cutters in the Bahamas. And most importantly, I’ve seen some of the best shipwrecks in the world, the historical time capsules at the bottom of the Great Lakes.

The five lakes shared by Canada and the U.S. harbor 21 percent of the world’s surface fresh water, and nearly every type of vessel man’s folly thought unsinkable… and I’ve visited them in their ghostly graves, with camera in hand, reverence in my heart, and a burning desire to bring back their haunting images and share them with whomever will look. I’ve seen romantic wooden schooners from the age of sail, giant steel behemoths thought too big to succumb to the inland seas, package freighters trying to earn a living as prehistoric semi-trucks moving people and goods from port to port, and I’ve seen them in all five Lakes. No small feat, only made possible by an obsessed drive to spend too much time on the road sleeping in fleabag motels, uncounted hours on boats in bad weather, too many trips to the edge of hypothermia, and the willingness to let go of all my disposable income for nearly two decades. I’ve been fortunate indeed.

Of all the shipwrecks I’ve had to strap on a steel tank to see, none hold as much importance to my personal journey as one who’s decks I once walked in Tee-shirt, shorts and sandals, beside my father as a young boy, the ALVIN CLARK. It wasn’t underwater, though it used to be. It was in Wisconsin’s Door peninsula, and was a floating museum ship during much of the seventies, waiting to spur on the imagination of impressionable future explorers. All I knew was when Dad and I pulled into the parking lot, her giant masts collected my gaze and channeled it down to a real life pirate ship! We didn’t stay too long, at least not by my standards, my father would more than likely say we had stayed plenty long, but someone snapped a photo of the two of us standing on her deck, and my father enlarged that photo into a 2 foot by 3 foot black and white poster. My parents were long since divorced, and I suspect it was his way of staying in my thoughts when I wasn’t with him. That poster hung on the wall of my bedroom until I left home many years later. I lost track of the poster, but I never forgot about that big wooden ship that I didn’t even know the name of.

Fast forward to my thirties, when I began scuba diving. I immediately fell in love with the shipwrecks that were right off the shores of my native Milwaukee, diving down to them as often as I could afford to pay a dive boat to take me. I soon tired of visiting the same old wrecks over and over, and began seeking out new destinations to satiate my shipwreck hunger, which meant reading books about shipwrecks, and that’s when I put 2 and 2 together, the pirate ship from my childhood memory was a lake schooner, and it had sunk a very long time ago. A bunch of rabid divers with the same affliction as me actually raised the schooner from the bottom and figured out her name. People like Frank Hoffman, Richard Bennett, Dr. Richard Boyd, some of whom would go on to become friends and colleagues of mine later in my life, and so many others I never met, through their infectious love of maritime history introduced me to my love of bygone sailing ships, wrecks and other sunken things. The nudge was so subtle, it was nearly imperceptible. A tiny seed planted in the fertile but dry soil of my imagination. It took nearly a quarter century for that seed, sowed the day I walked the decks of a pirate ship to sprout when I added water to it. Even as it grew, I didn’t understand where it came from, or where it was leading me.

I never set out to be a shipwreck photographer. I never dreamed I would become an ambassador of shipwrecks. I just started taking pictures underwater because I loved being a photographer on land, and the natural progression was to take a camera under the waves with me sooner or later. I quickly learned that the most impressive thing to image in the Great Lakes was a shipwreck. I also learned my new favorite thing was showing a non-diver one of those pictures. They would look at it in awe, and exclaim disbelief that these incredible things were ‘down there’. We then would talk about how clear the water could be and that there were a bunch more of these things ‘down there’ waiting to be found. I thus began an odyssey of spreading the shipwreck gospel to those not in the know. It led me to my position as a board trustee with the Wisconsin Marine Historical Society, to become a published writer and photographer, and an internationally recognized public speaker. Most of my best friends I have met through diving. Many of my greatest achievements, and most intense life (and sometimes near death) experiences were born of my love of diving on shipwrecks. I have been fortunate.

Sometime around my fiftieth birthday, my father stopped by the house with some things he wanted gone from his basement. They had been stored ‘down there’ for decades and he no longer wished to be their custodian. One item was a very large ship model of the USS CONSTITUTION, a square rigger, and salty, but a sailing ship nonetheless. I had built it as a young teenager, not many years after walking the decks of the ALVIN CLARK. The other item Dad brought over was something long thought lost, but never forgotten, a poster of a boy and his father.

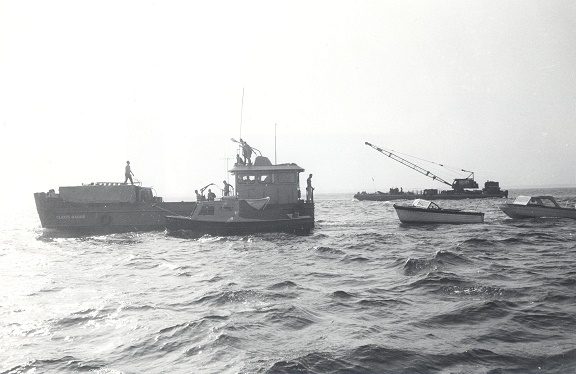

ALVIN CLARK Salvage Operations, Summer 1969.

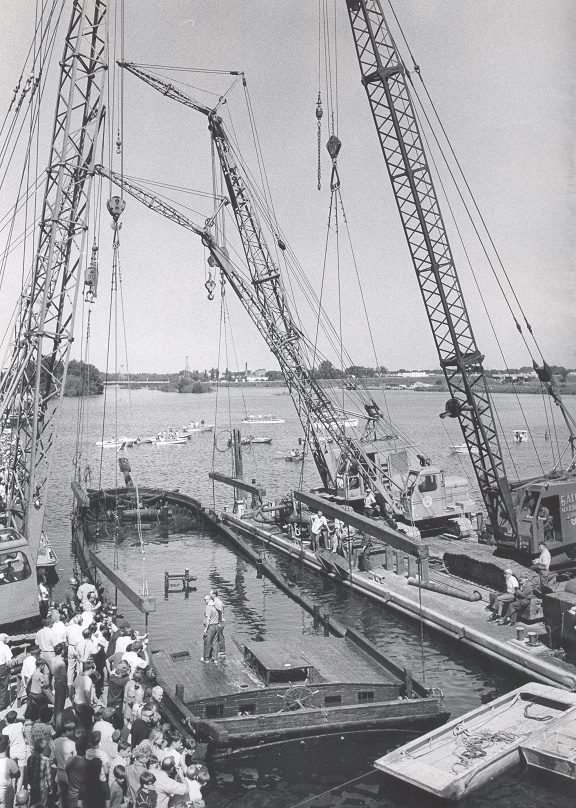

ALVIN CLARK being raised with cranes, July 1969.

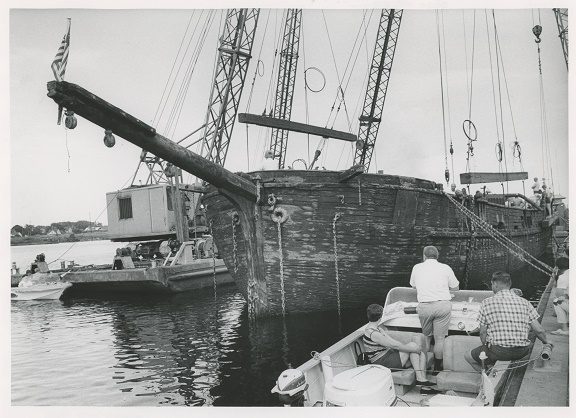

ALVIN CLARK between the dock and a barge, July 1969

ALVIN CLARK, dated 1969.

———————————————–

Cal Kothrade is the Shipwreck Ambassador of the Wisconsin Marine Historical Society, a diver, a photographer and an artist. His work can be viewed at www.calsworld.net

Photo Credit: Great Lakes Marine Collection of the Milwaukee Public Library and Wisconsin Marine Historical Society.

This story was originally posted on June 29, 2024.