By James Heinz

Milwaukee’s port facilities are centered on the peninsula known as Jones Island. Today it is totally industrialized. No one lives there. The only sounds you hear all year long are the sounds of a busy port. But once a year on the first Saturday of August a distinctive sound floats through the air of Jones Island:

Polka music.

In 1872 a man named Jacob Muza arrived in Milwaukee. He was a Kashube from Northern Poland. The Kashubes made their living as fishermen because they lived on the Hels Peninsula, which is a long, narrow sandbar sticking out into the Baltic Sea that is only 300 feet wide at its narrowest point. And what did Muza find when he arrived in Milwaukee?

A long, narrow sandbar sticking out into Lake Michigan that was only 300 feet wide at its narrowest point. It was like deja-vu all over again. Muza reportedly took one look at Jones Island and said, “FISH”!

Muza had come to America to escape political and cultural repression by Germans. And what did he find when he arrived on Jones Island? Germans.

Together the two ethnic groups began the settlement of the deserted sandy wasteland that was Jones Island. According to local historian John Gurda, “there were 12 dwellings on the peninsula in 1875, 20 in 1880, and more than 300 by the 1890s.” The population of a place where today no one lives soared to 1,600 by 1900.

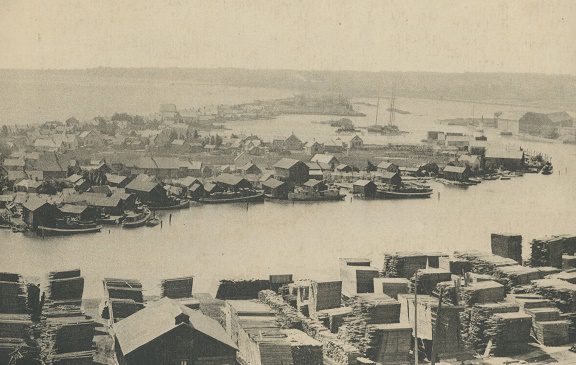

Jones Island Settlement with Wolf & Davidson shipyard across the river. WMHS/MPL Photo

The Kashubes turned immediately to fishing, at first using small sailboats like the Mackinac boat I described in an earlier article, and then steam powered tugboats which with the introduction of gasoline and diesel engines eventually evolved into the pointed shoebox shape of modern Great Lakes commercial fishing boats, which is why fishing boats on the Great Lakes are called fish tugs.

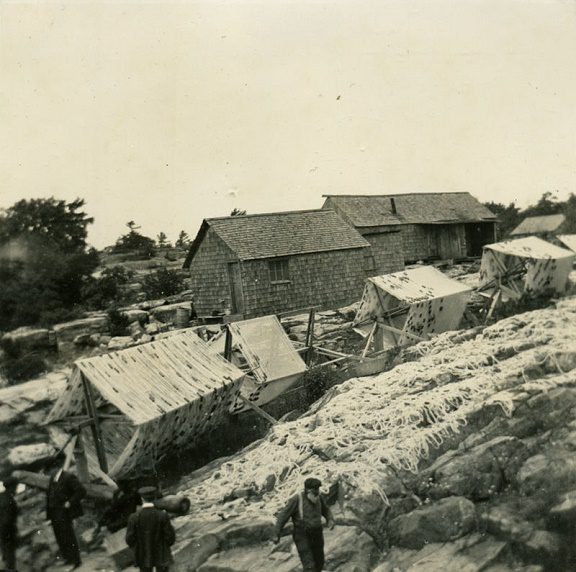

Fish nets drying. Courtesy of Wikepedia

The Kashubes built their own community on the Island. In Poland the Kashubes lived a communal lifestyle with no defined hierarchy and they continued that tradition in America. No one was really in charge of their community. The nearest thing to a mayor that they had was Jacob Muza, because he had arrived first.

Because no one was in charge, and because the City of Milwaukee government ignored them, their settlement grew into a haphazard collection of clapboard houses, fishing sheds, and other structures built more or less at random. It was a place of crooked “streets” and paths that often went nowhere.

Imported school teachers. Courtesy of Wikipedia

There were no paved roads on the island, no indoor plumbing, telephones, or electricity, no police or other government services until 1896 when the City noticed that there 110 children on the Island who were not going to school because there was no school. That year the City established a school described as “a barracks”. The schoolteachers were rowed across the inner harbor from the National Avenue dock because there were no roads on the Island.

Having caught the fish, the Kashubes had to sell it to make a living. They sold the fish to dealers on the mainland. But they also established several examples of Milwaukee’s most important institution: taverns.

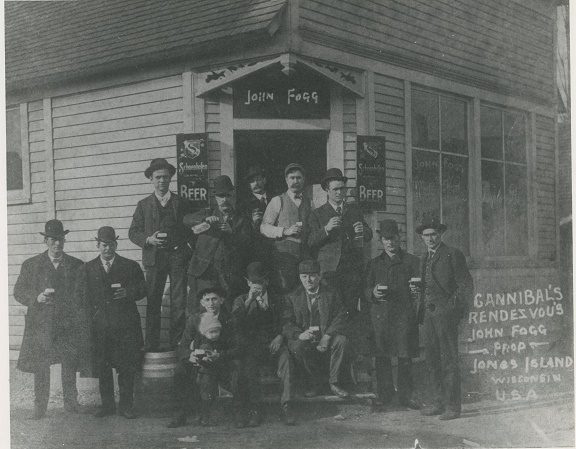

John Fogg’s Cannibal’s Rendezvous. WMHS/MPL photo

One of these taverns was called The Cannibal’s Rendezvous. (Apparently, fish was not the only food served to visitors.) And at these taverns they established one of Milwaukee’s most revered and sacred traditions: the Friday fish fry.

Mainlanders could catch a boat trip from downtown piers to the Island, where small boys stood by willing to guide visitors through the tangled maze of streets and paths to a tavern serving fried fish that had been pulled out of the Lake only hours before.

Photo at top: Island looked like a reversed letter P . WMHS/MPL photo

Eventually, the Kashube community was threatened with extinction by the forces of Big Business. The Island looked like a reverse capital letter “P”, with the larger end of the P at the north end. The Kashubes had the north end of the Island all to themselves. The south end was occupied by a steel mill operated by the Illinois Steel Company. In 1896 the company began an effort to evict the Kashubes.

And at this point the reason the City had not provided any city services to them became clear. The Kashubes did not receive services because they paid no taxes because they did not own the land they lived on. They were squatters who had simply settled on vacant land and assumed that they owned it.

The steel company used a variety of tricks to convince illiterate Kashubes to sign papers giving up their land. Several attempts by constables to serve eviction papers were physically rebuffed by angry Kashube housewives with such vigor that the constables became afraid to serve more eviction notices.

The Kashubes used a legal concept known as Adverse Possession, or in layman’s terms “squatters’ rights” to defend their property. The Kashubes had made improvements to the land by filling it in and building structures on it. In 1901 a jury answered the question: Who owned Jones Island? The answer: Nobody.

The jury reasoned that because the Island had once been underwater, it should be considered land reclaimed from the Lake bottom and by law it therefore belonged to the State of Wisconsin. This decision largely stopped the evictions.

However, the Kashube community started to dwindle away. The work was hard and dangerous, particularly in the winter. The Kashubes traditional resistance to authority led them to disregard conservation laws and the resulting overfishing led to the depletion of fish stocks. And finally, the Kashubes were overcome by the one force none of us can resist.

Government.

The City of Milwaukee, having long ignored the island, began to build things on it and wanted to build more. In 1920 the City paid many of the families for their land that the families did not actually own. That year only 28 families lived on the Island; by 1922 only 8.

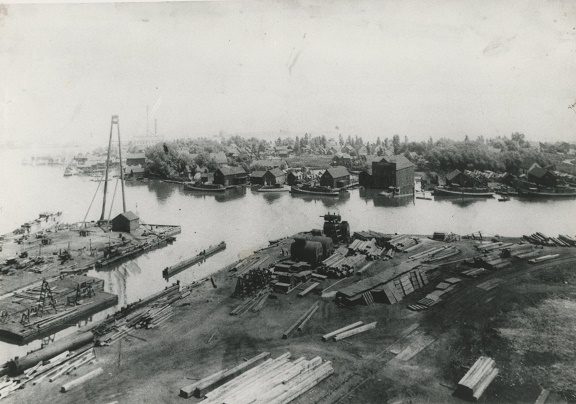

Jones Island settlement in 1939. WMHS/MPL photo

The last Kashube to leave the island was Captain Felix Struck, who claimed to be the first child born on the Island and who ran a tavern on the west side of the Island. He was evicted in 1943 as a security risk. The Kashubes vanished, a community forgotten by everyone except their descendants.

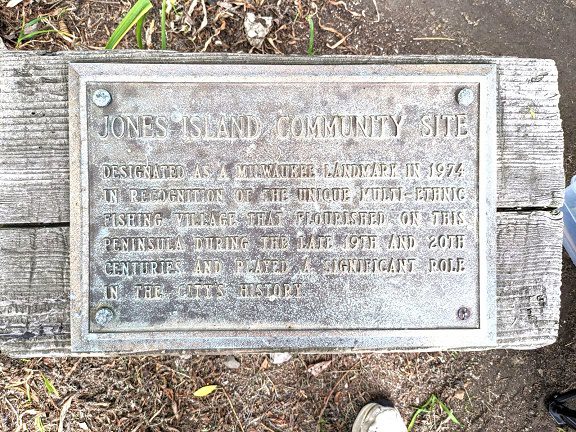

In 1974 the Kashube descendants persuaded the City to establish Kaszube Park on the site of Felix Struck’s saloon. The 0.15 acre park is an island of green grass and mature trees in a barren industrial wilderness. Every year on the first Saturday in August, the descendants gather to remember their ancestors and the community that is gone but not forgotten.

And the distinctive sound of polka music floats through the air of Jones Island.

2023 reunion at Kaszube Park. Photos by James Heinz.

____________________________________

James Heinz is the Wisconsin Marine Historical Society’s acquisitions director. He became interested in maritime history as a kid watching Jacques Cousteau’s adventures on TV. He was a Great Lakes wreck diver until three episodes of the bends forced him to retire from diving. He was a University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee police officer for thirty years. He regularly flies either a Cessna 152 or 172.