WHAT HAPPENED TO MY TITANIC PASSENGER?

By James Heinz

Recently the WMHS blog ran a three part story that I wrote about a Milwaukee ship owner who died on the TIITANIC while trying to conceal a sex scandal. We scheduled our posting of that story to coincide with the run of the play “TIITANIC: The Musical” at the Milwaukee Rep. Unfortunately, the play was suspended for it final few weeks when the entire cast caught Covid. The play will resume September 23 to October 23, 2022.

Three friends and I attended the play. I highly recommend it. It is not totally historically accurate but hey, it’s a musical, not a documentary.

But one thing that is historically accurate occurs before the play even starts. Attendees are given a faux boarding pass with the name and data of a real passenger or crew member. We waited until we returned home to find out what happened to the persons on our boarding passes.

My passenger was a humble second class passenger named Edward Beane. By 1901 he was working as a bricklayer in Norfolk, England. He came to America in 1907 and returned to England in 1910 to find a bride.

In March 1912 he married 23 year old Ethel Louisa Clark, who had lived on the same street in Norfolk that he had lived on. They had known each other since childhood. She promised to wait for Edward until they had saved up enough money for a nest egg.

Edward had crossed the Atlantic in steerage the first time, but this time he booked second class passage on the TIITANIC, buying ticket #2908 for 26 English pounds at Southhampton a couple of days before TIITANIC sailed.

They felt the impact of the iceberg but thought nothing of it until another passenger told them of the order to dress and get on deck. Edward persuaded Ethel to leave their nest egg in the purser’s safe.

The Beane’s survived the sinking and settled in Rochester, New York, where they lived until they died. They only gave a few interviews between 1912 and when Edward died in 1948 and Ethel in 1983. And the reason they both survived may be the reason they gave few interviews.

In the 1900s Edwardian era, it was expected that men would give up their lives to save women. According to Wikipedia, Benjamin Guggenheim, one of the world’s richest men, said the following aboard the TIITANIC: “I am willing to remain and play the man’s game if there are not enough boats for more than the women and children…No women shall be left aboard this ship because Ben Guggenheim was a coward.”

Guggenheim did go down with the ship and Mrs. Guggenheim may have admired her husband’s courage, but was less likely to have admired him for having said this after he put his French mistress in the lifeboat.

So the fact that Edward was one of the few second class males to survive, leads to questions about how he did it. Part of the confusion is the fact he gave different stories about how it happened.

Ethel boarded lifeboat #13. One would think that getting on board a lifeboat being lowered from a sinking ship would mean the occupants were safe, but in fact their danger was just beginning.

Wikipedia says “While it was being lowered, boat 13 was nearly swamped by “an enormous stream of water, three or four feet in diameter” coming from the condenser exhaust which was being produced by the pumps, far below, trying to purge the water that was flooding into TIITANIC. The occupants had to push the boat clear using their oars and spars and reached the water safely. The wash from the exhaust caused the boat to drift directly under lifeboat number 15, which was being lowered almost simultaneously. Its lowering was halted just in time, with only a few feet to spare. The falls aboard lifeboat number 13 jammed and had to be cut free to allow the boat to get away safely from the side of TIITANIC.”

The website norfolktalesmyths.com says that Ethel said that she lost sight of her husband in the loading and hoped he had made it to another boat. Edward claimed that he had jumped into the water and swam “for hours” before being pulled into lifeboat #13. No one on #13 remembered pulling anyone from the water. Also, no one could have survived the freezing water for more than a few minutes.

Edward also claimed that he swam until he was picked up by lifeboat #9 and was reunited with Ethel aboard the rescue vessel CARPATHIA. No on one lifeboat #9 remembered picking him up, and he is listed as being in lifeboat #13 when it was recovered.

The fate of another lifeboat #13 passenger offers a clue. When men jumped into #13, contrary to the women and children only orders, the TIITANIC’s officers ordered them out. One of the female passengers took pity on one of them and pushed him down into the bottom of the boat and covered him with a shawl to conceal him.

That or something similar is probably what happened to Edward. Since lifeboat #13 was only half full, no woman was left aboard the ship because Edward Beane was a coward, but the Beane’s may have felt compelled to hide the fact that Edward had not played the man’s game by the rules of the Edwardian era.

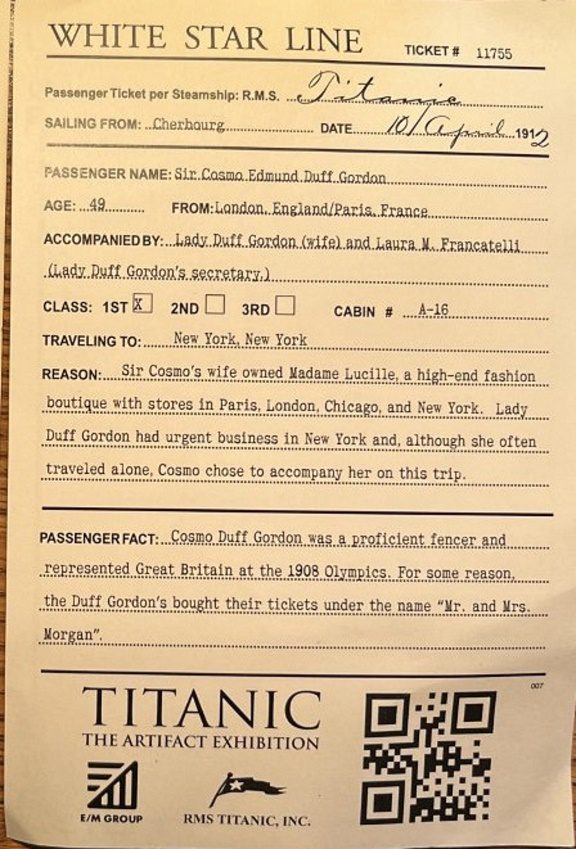

One of my companions was issued a boarding pass in the name of Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon, another passenger who would survive under controversial circumstances. His name alone makes him stand out, since the only other person I ever heard of named Cosmo was the fictitious Cosmo Kramer on Seinfeld.

Sir Cosmo was a Scottish aristocrat, landowner, and sportsman, being a noted fencer and wrestler. He, his wife, and her secretary occupied cabin A16.

After TIITANIC hit the iceberg and her crew began loading the lifeboats, Sir Cosmo and his wife and her secretary approached First Officer Murdoch, who was supervising the loading of lifeboat #1. According to the Duff-Gordon’s testimony, Cosmo asked Murdoch if he could get in the lifeboat with the women, and Murdoch agreed, although this violated the women and children first order. Lifeboat #1 was lowered with only 12 people on board.

When it was suggested later that the boat return to pick up people struggling in the water, Lady Duff-Gordon warned that they might be swamped if they did so. It was then decided that they should row towards a light they could see in the distance.

As they did so one of the crewmen complained that he and the other crew had lost all their belongings in the sinking, and they would have no money to buy new things since their pay was stopped at the moment the ship sank. Sir Cosmo then promised to give 5 English pounds to each of the crew men when they reached safety, which he did when they were aboard the rescue ship CARPATHIA.

This at least is what Sir Cosmo said at the official inquiry. Others interpreted his actions differently.

Sir Cosmo’s actions were interpreted by others as, first of all, violating the Guggenheim Principle: that men should go down with the ship to save the women. Although lifeboat #1 was lowered with less than half its capacity, and therefore no one could accuse Sir Cosmo of having taken the place of a woman who could otherwise have been saved, many people thought that Sir Cosmo had done something wrong by the standards of the time.

In addition, the money that Sir Cosmo gave to the crew to replace their lost belongings was interpreted as a bribe that Sir Cosmo paid them to persuade them not to return to pick up survivors in the water.

Although witnesses testified that Murdoch had allowed Sir Cosmo into lifeboat #1, and most of the people in the boat were not in favor of returning to pick up the survivors in the water, one comment Sir Cosmo made may have prejudiced others against him. According to Titanic.famdom.com, when asked if the lifeboat should return to pick up those in the water, the crew members said that Sir Cosmo answered: “Let them swim for they don’t have the pockets of a rich man weighing them down.”

It’s kind of hard to put a positive spin on that statement.

Although the official British inquiry, consisting entirely of upper class Englishmen, cleared Sir Cosmo of any wrong doing, it also cleared every other upper class Englishman of any wrong doing, including the ship’s owner who had not put enough lifeboats on an ocean liner that he insisted proceed at high speed on a dark night through a sea full of icebergs and who had also violated the women and children first order in order to save his own life. Instead, the inquiry blamed the captain of the steamer CALIFORNIAN (the nearest ship to the TIITANIC), who had the misfortune to not be an upper class Englishman. Exoneration by the official inquiry did not mean much to many people.

The Duff-Gordon’s spent the rest of their life tainted by their survival. Sir Cosmo would later say: “There seems to be a feeling of resentment against English man being saved…the whole pleasure of having been saved is quite spoilt by the venomous attacks they made at first in the papers…This, I suppose, was because I refused to see any reporter.”

The reporters, or course, did not have the pockets of a rich man to weigh them down.

You can still remember Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon when you drink a glass of Duff-Gordon sherry, which his family made at the time and still do to this day.

Since we have covered two men who survived the TIITANIC under what were considered questionable circumstances at the time, we might as well continue in the same vein with the third boarding pass that one of my party was issued: Dr. Henry Frauenthal.

Dr. Frauenthal, the American son of an immigrant shoe salesman, first obtained a degree in inorganic chemistry and then went on to obtain a medical degree. He and his brother became specialists in the treatment of joint conditions and founded their own hospital to treat those conditions. Frauenthal himself was also a pioneer in the use of color photography in medical treatment.

Frauenthal’s experience aboard the TIITANIC is only sparsely documented, possibly because what happened to him afterward attracted more attention. Two weeks before the voyage he married a woman in France. Frauenthal and his bride were first class passengers, having paid 133 English pounds for ticket #PC 17611. His brother Isaac joined him aboard at TIITANIC at Cherbourg.

The next we hear of them is when Frauenthal and his brother jumped into lifeboat #5, which was being lowered by First Officer Murdoch and none other than J. Bruce Ismay, owner of the TIITANIC himself. Ismay, clad in pajamas and slippers, urged one of the crew to begin loading women and children. The crewman, who either did not recognize Ismay or was unconcerned about his future employment prospects, told Ismay that he only took orders from the captain. Eventually the loading of mostly women and children began and the lifeboat was lowered.

Wikipedia tells us: “The boat’s progress down the side of the ship was slow and difficult. The pulleys were covered in fresh paint and the lowering ropes were stiff, causing them to stick repeatedly as the boat was lowered in jerks towards the water. Ismay sought to spur those lowering the boat to greater urgency by calling out repeatedly: “Lower away!” This resulted in [a crewman] losing his temper: “If you’ll get the hell out of the way, I’ll be able to do something! You want me to lower away quickly? You’ll have me drown the lot of them!” The humiliated Ismay retreated up the deck. In the end, the boat was launched safely.”

Frauenthal’s wife was placed in the lifeboat, and Frauenthal, his brother, and two other men jumped in as it was being lowered. A female passenger complained that a doctor and his brother jumped into the boat and that the doctor, who she described as weighing 250 pounds, landed on her, knocked her unconscious and dislocated two of her ribs. Historians suggest that the female passenger may have mistaken another passenger for Frauenthal, and that she may have exaggerated her injuries.

When he returned home, his hospital gave him a reception. Frauenthal wrote an article for a medical magazine about his TIITANIC experience. He and his wife were plagued with mental and physical health problems for the rest of their lives. Frauenthal committed suicide in 1927 by jumping from the seventh floor of his own hospital. Although his TIITANIC experience may have left him feeling PTSD and survivor’s guilt, his family believes that he killed himself because he wanted to avoid any more diabetes related amputations. His wife spent the rest of her life in a mental asylum suffering from depression.

Oddly, Frauenthal’s will stipulated that he be cremated and that his ashes would be scattered to the wind from the roof of his hospital exactly fifty years after his death, which was done. The hospital he founded, the Hospital of Joint Diseases, still exists as the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases.

Most of the passengers on TIITANIC were humble poor people, like the Beane’s. By chance, my party received boarding passes for three prominent people. And since all of our previous stories have been about men who violated the Guggenheim Principle, we might as well end with one.

Paul Romaine Chevre was a French sculptor who made it big in Canada. He would spend six months of the year in his Paris studio, and the other six months in Canada. He made several large sculptures of notable Canadians which still stand, the most famous of which is a statue of the explorer Samuel des Champlain, which still stands in Quebec City.

By coincidence, Chevre was commissioned to produce a statue by Charles Hays, manager of the Grand Trunk Line, whose interaction aboard TIITANIC with Milwaukee TIITANIC victim Edward Crosby I covered in a previous blog story.

Chevre was a first class passenger. He paid 28 English pounds for ticket number PC 17594, in Cabin A-9

On the night of April 12, 1917, Chevre was playing cards in, where else for a Parisien, the Café Parisien. When the ship stopped, at first he thought it was too cold to go outside. Although the incident did not appear to be serious, he decided to board lifeboat #7. By another incredible coincidence, this was the same lifeboat containing the wife and daughter of Edward Crosby.

Accounts vary as to whether the women and children first order was obeyed in the loading of lifeboat #7. One interpretation is that the order was obeyed at first but then bystanders urged the crew to let married men aboard with their wives and then any man was allowed aboard. #7 was still lowered with only 28 or 29 people on board. #7 was the first lifeboat to be lowered.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of TIITANIC is that the ship’s officers lowered the lifeboats half empty because they believed that the boats could not take the strain of a full load of 70 people. They intended to lower the boats half empty and then pick up more passengers from doors in the side of the ship later. In fact, the lifeboats had been tested successfully with a full load but this information was not relayed to the crew, and nobody aboard the lifeboats wanted to go back.

At any rate, Chevres and his male companion got on board lifeboat #7. One source says that they were “chided” by friends for getting in the boat. The source does not say if they were chided for leaving the ship, since at this point most people did not realize that TIITANIC was going to sink, or for not obeying the Guggenheim Principle. Chevre said an officer asked him to board the boat to set an example for others.

Lifeboat #7 leaked because the drain plug had not been put in, and the leak was stopped by stuffing women’s garments into it. It drifted for hours with the passengers feet submerged in icy water.

When he arrived in New York Chevre gave an interview to a reporter who filed a sensational story, which was repeated worldwide, including the claim that Chevre heard Captain Smith proclaim “My luck has turned” and then committed suicide by shooting himself.

This story, which is described as “a total fabrication by a reporter who either didn’t speak French or made the whole thing up to sell papers,” was angrily refuted by Chevres when he arrived in Montreal. Chevres described the story as “a tissue of lies”. The Herald insisted it did not invent the story but said that since its reporter did not understand French very well he must have misunderstood what Chevre said.

Chevre died in Paris in 1914. At his death the Montreal Gazette said: “Paul Chevre was a passenger on the ill-fated TIITANIC and although he survived the shock, it is doubtful that he ever recovered from it.”

Something which could have been said of all the men for whom we received boarding passes.

____________________________________

James Heinz is the Wisconsin Marine Historical Society’s acquisitions director. He became interested in maritime history as a kid watching Jacques Cousteau’s adventures on TV. He was a Great Lakes wreck diver until three episodes of the bends forced him to retire from diving. He was a University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee police officer for thirty years. He regularly flies either a Cessna 152 or 172.

Photo at top of page: White Star Line ticket for Sir Cosmo Edmund Duff Gordon.

Other photo:

Photos of tickets provided by James Heinz.