By James Heinz

In a previous article I recounted how a U.S. Lifesaving Service surfman earned the gold Lifesaving Medal rescuing a man from the top of Milwaukee’s Love Rock in the middle of a raging storm at risk of his own life. Today I tell how he overcame even greater difficulties to rescue another man from a sunken ship off the Milwaukee shoreline.

Ingar Olsen was born in 1870 in Holmsbu, Norway. Much of what we know of his life comes from his personal scrapbook in the files of our sister organization the Milwaukee County Historical Society. The scrapbook consists mostly of undated newspaper articles and does not give us a full picture of his life.

He seems to have developed the habit of rescuing people early in life. When he was 11 years old, he and a companion rescued two people from a capsized skiff in a Norwegian harbor. For this feat of bravery, he and his friend were awarded by the Norwegian government a sum of Norwegian currency worth $2.67. At age 15, he went to sea on square rigged sailing ships as a cabin boy.

Olsen said he first came to America and Milwaukee at the age of 17 in 1887. He sailed on Lake schooners for three seasons. He enlisted in the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service in 1890. At that time what is now the U.S. Coast Guard as we know it, did not exist. There were four separate government agencies that did what the unified U.S. Coast Guard does today: the Revenue Cutter Service, the Lifesaving Service, the Lighthouse Service, and the Steamboat Inspection Service.

Olsen was assigned to the Revenue Cutter U.S.R.S ANDREW JOHNSON, based in Milwaukee. After one year he transferred to the Lifesaving Service and was assigned to the Milwaukee station. In 1893 two significant things happened in his life:

He saved a man’s life at great risk of his own on top of what would later become known as Love Island or Love Rock and was awarded the gold Lifesaving Medal in Washington D.C. for his actions.

The other was his proposed promotion to commander of the Milwaukee lifesaving station was stopped due to objections from the Lake Seaman’s Benevolent Association on the grounds that Olsen was not qualified because he was not a U.S. citizen and could not speak English. The man whose life Olsen saved on top of Love Rock had not found him unqualified.

When asked, what was the hardest and most dangerous rescue he had ever performed, he did not mention the Milwaukee crib rescue. Instead, he said it was the rescue of the crew of the schooner M. J. CUMMINGS off Milwaukee on May 18, 1894. And once again, just like the 1893 crib rescue, he did it in front of a crowd of thousands of spectators on Milwaukee’s lakefront.

On that day a severe storm was blowing across Lake Michigan. A drop in temperature of 50 degrees in 24 hours had caused 60 mile an hour winds and high waves. Thirteen schooners were dragging their anchors and flying distress signals even though they were inside the Milwaukee harbor and were in no danger.

One schooner that was in danger because it was not inside the harbor was the M. J. CUMMINGS. WMHS files show that she was launched in 1874 in Oswego NY. The CUMMINGS was 330 gross tons and was 137 feet long and 26 feet wide.

She tried to get into the harbor but could not so she anchored just south of the piers that then went out into the Lake on either side of the Milwaukee River. The anchors, however, did not hold, and the ship drifted down towards the south end of Jones Island, flying the American flag upside down as a distress signal.

The tug SIMPSON, seeing the CUMMINGS drifting, came out and tried to pass a line to the schooner, but huge waves came aboard the tug and poured into the engine room, threatening to put out her boiler fires and the tug had to return to the harbor to save itself.

The CUMMINGS’ Captain John McCulloch then ordered his crew to cut a hole in the bow and the hatch covers removed in an effort to sink his ship.

Normally, ship captains try to avoid sinking their ships, much less doing so intentionally. The severity of the storm and the desperation of the crew can be gauged by the fact that the captain had decided to scuttle his ship in an effort to save both his crew and his ship. By sinking the schooner intact, he avoided having it thrown onto the shoreline and smashed into pieces and the crew tossed into the raging surf.

The storm, however, slammed the stern down so hard that when it struck the bottom, the rudder was driven up through the hull, creating a big hole through which water rushed, sinking the ship in 18 feet of water half a mile from shore. The crew of six men and one woman cook then climbed up into and tied themselves to the rigging, of the masts, which stuck out of the lake above the sunken schooner.

The Milwaukee lifesaving station had seen the CUMMINGS distress signals from the tower at their Jones Island station. The lifesavers had been following the schooner with their beach apparatus, and when they saw it sink, they tried firing a line out to it with their Lyle gun, but the range was too great.

Station commander Captain William Pratton then tried to do what they had done in the 1893 crib rescue, get a tugboat to tow the station lifeboat out to the disaster. All the tugboat captains refused, except for Captain John McSweeny of the tug HAGERMAN, who offered to tow the boat, but wanted to wait until a steamer entering the harbor had passed. Captain Pratton did not feel that he could wait.

So, at 10 am Captain Pratton and his crew decided to row out to the wreck, with Ingar Olsen pulling on one of the oars. They were about to live out the motto of the Lifesaving Service: “You have to go out. You don’t have to come back.”

As the lifeboat closed on the sunken schooner stern first, a huge wave lifted the lifeboat up and slammed it into the main mast, then the mizzen mast, and finally onto the submerged rail of the sunken ship. The impact was so violent that Captain Pratton was thrown overboard on one side and surfman Frank Gerdis on the other side. Olsen and his boatmate Charlie Carland pulled Pratton out of the Lake.

Gerdis was able to swim to the mizzen shrouds. Gerdis then tried to secure a line from the lifeboat to the rigging, but the storm broke the line. He then climbed into the rigging, wrapping torn sails around the woman cook tied to the port mizzen shroud in an effort to keep her warm, and tied the captain and mate to the fore shroud.

Three or four oars had broken in the collision, and two of the oarlocks had been damaged. The crew then deployed their spare oars, but while they were doing that the boat drifted 200 feet astern. The crew then tried rowing back to the CUMMINGS, but another wave overturned the boat, pitchpoling it end over end with Carland trapped underneath the capsized boat, according to Olsen. Surfman Reinerson was then swept away by a wave and drifted off towards the shore, helpless in the raging water.

According to Olsen’s recollection, the remaining crew were able to right the boat but, in the process, Captain Pratton was hit on the head by the boat and knocked unconscious. The surfboat was made of oak and mahogany, was 28 feet long, and weighed 4,000 pounds.

The capsizing meant that all of their oars, ropes, and equipment were lost. The surfboat then drifted ashore. Olsen said that the boat crew rescued Reinerson by making a human chain in the surf to pull him ashore.

The lifesavers returned to their station, and Captain Pratton directed a bystander to take a message to a nearby telegraph office asking that a telegram be sent to the Racine lifesaving station asking that they respond with their lifeboat. The Racine lifesavers arrived around 3 pm but the message had been garbled and instead of their lifeboat they brought their 26 foot surfboat, which was too light to survive the storm.

At this point the boat crew was depleted. Gerdis was still in the rigging, and Carland, Reinerson, Captain Pratton, and one other surfman were physically unable to do anything. That left only Olsen and three other men to try to do what nine men had failed to do.

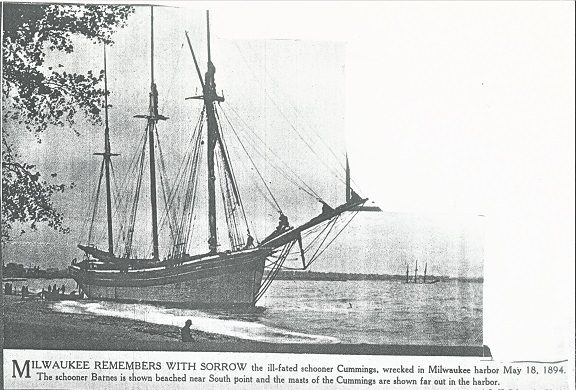

What was left of the crew then departed with their beach gear and Lyle gun to the south end of Jones Island, where the schooner BERTHA BARNES was seen dragging its anchors as it drifted toward the beach. However, the BARNES dropped her anchors and the storm threw her so far up on the beach that her crew was able to jump overboard onto dry land.

When they returned, Olsen said that Surfman Henry Sinnegan obtained a normal small boat from the SS NEBRASKA to replace the damaged surfboat. According to Olsen, the remaining crew then appealed to the thousands of people lining the shore who had gathered to watch the unfolding disaster to volunteer to help them

Not one person volunteered.

By this time the lifesavers left to man the NEBRASKA’s boat were Pratton, Olsen, and two of the Racine lifesavers. The other crew members were not notified for some reason never made clear.

Captain John McSweeny of the tug HAGERMAN then agreed to tow the NEBRASKA’s boat out to the CUMMINGS behind a gravel scow. The plan was to use the gravel scow as a kind of floating breakwater behind which the NEBRASKA boat could shelter as it approached the CUMMINGS.

However, the NEBRASKA boat damaged its bow in a collision with the scow and started to fill with water. The lifesavers felt that they could not row a boat half full of water, and so the boat was allowed to drift empty at the end of a line down to the wreck of the CUMMINGS.

And then the most heartbreaking part of this saga occurred: Three of the crew of the CUMMINGS had by this time fallen out of the rigging and drowned, and two others, including the woman cook, were dead, having frozen to death while lashed to the rigging. Only Gerdis, the CUMMINGS’ first mate, and a CUMMINGS crew member named Patterson were left alive in the rigging of the sunken ship.

By the time the NEBRASKA’s boat reached the sunken schooner, it was half full of water from the hole in the bow. The first mate at first refused to jump into it, and when he did jump, mistimed the jump and fell into the Lake and drowned. Gerdis and Patterson were able to jump into the boat as it drifted over the wreck. They then found that the boat was entangled in the rigging in such a way that they could not row back to the scow, so they cut the rope to the scow and used their oars to steer the boat to the beach, which they reached around 5:30 pm. Patterson had been in the rigging for seven hours.

The storm blew for eight days, and was so bad that only on the third day were the lifesavers able to go out and look for the bodies, according to Olsen.

Captain Pratton was investigated by the Lifesaving Service for his conduct during this event and removed from his command. You would think that going out into a raging storm, being swept overboard, and then getting hit on the head by a two-ton boat would be sufficient proof of his devotion to duty, but the Lifesaving Service disagreed.

Their official report, which I found in the WMHS files, faults Pratton for not waiting for the HAGERMAN the first time, for drifting down upon the CUMMINGS without a plan, for not anchoring and then drifting down, for using the rudder and not a steering oar, for not passing Gerdis a stronger rope, for not sending the telegram to Racine himself to avoid miscommunication, for not formulating another plan while waiting for the Racine lifesavers to arrive, for not notifying the rest of the lifesavers to assist with the NESBRASKA boat, and for using the NEBRASKA’s boat instead of his own lifeboat.

The investigation was begun after complaints by some of the thousands of people who had watched from shore and refused to help, but who were outraged that five people died while they had watched and done nothing. The only good thing about the thousands of people on the shoreline who refused to help was that one of them was the woman who would later marry Ingar Olsen.

Ingar Olsen remained in the Lifesaving Service. He responded to about 1,500 rescue calls. In 1897 he married one of the people who had seen him struggle to save the crew of the CUMMINGS and they had two sons. He was later stationed at Plum Island Wis. and Washington Island Wis.

In 1901 he gained his revenge on those who thought he was unqualified to be station commander at Milwaukee by being appointed station commander at Milwaukee. He remained in service and was promoted to warrant officer in 1915, the same year the unified U.S. Coast Guard was established. He retired in 1920 and lived with his wife in Shorewood Wis. until his death in 1964 age 94. His wife Emily Tewes Olsen followed him in 1966. They are both buried in Wisconsin Memorial Park in Brookfield Wis.

As for surfman Frank Gerdis, he stayed with the Lifesaving Service until 1903 when he quit and became a Milwaukee bridge tender until he retired in 1930. He died in Milwaukee in 1940 at his home on South Shore Drive, within sight of the Lake which had almost killed him. He is buried in Forest Home Cemetery.

Photo: BERTHA BARNES on shore with M. J. CUMMINGS sunk off shore. Photo from unknown newspaper.

____________________________________

James Heinz is the Wisconsin Marine Historical Society’s acquisitions director. He became interested in maritime history as a kid watching Jacques Cousteau’s adventures on TV. He was a Great Lakes wreck diver until three episodes of the bends forced him to retire from diving. He was a University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee police officer for thirty years. He regularly flies either a Cessna 152 or 172.

This story was originally posted on May 18, 2024.