By James Heinz

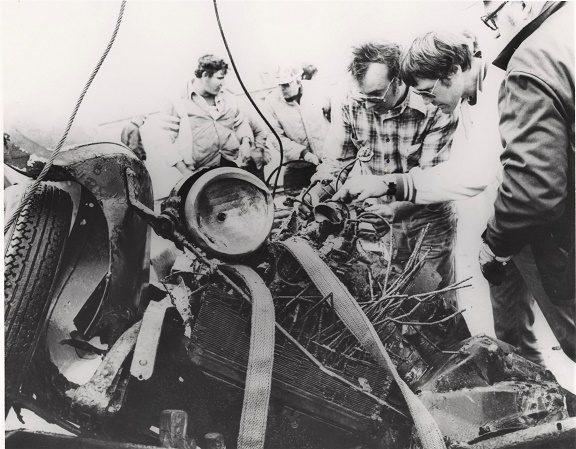

Although Butch did not bring up a gold Gold Bug, he did participate in the retrieval of another car from the LAKELAND. As Wisconsinshipwrecks.org notes: “In the late 1970’s, a 1924 Rollin car was salvaged. Because of serious problems while salvaging, the car ended up in a garbage dump.”

As you might have guessed from reading this story so far, Butch Klopp was involved, along with John Steele and Kent Bellerichard. Jason said that they lifted the car off the wreck with a lift bag and began towing it back to shore. However, the vehicle dropped off the lift bag so they towed it along the bottom until they got it to shore. The car was too badly damaged to restore and was scrapped.

I can confirm this story because many years ago I saw a film about the recovery of this auto. It was dragged up a boat ramp and placed in a parking lot. My recollection is that the exposure of the rusty steel to the oxygen in the air caused the car to crumble into dust as it sat there, until only the axles, drive train, and wheels were left.

Butch also loaned many artifacts to the Rogers Street Fishing Village in Two Rivers, as mentioned in my previous article on the Christmas Tree Ship, the schooner ROUSE SIMMONS. And after his death his family donated 10,100 of his artifacts to the Wisconsin Maritime Museum in Manitowoc. This donation was so large that it doubled WMM’s artifact collection and accelerated WMMs plans to renovate its off-site storage facility in downtown Manitowoc to house and conserve the Klopp Collection. More on that in a future article.

In addition to protecting his community from crime, Butch also protected it from both a total loss of electrical power and from dying of thirst. Jason told me that the water intakes for the lakeside power plant and the city water plant in Port Washington would often freeze up in the winter. Butch would use his steel hulled boat as an icebreaker to break up the surface ice, and would dive down to chop ice out of the city water intake by hand.

Which brings us back to 302 South Division Street on the morning of December 12, 2022. It was a balmy 27 degrees that day. As a former police officer, I recognized The Usual Suspects of Great Lakes underwater archeology: Kevin Cullen and Cathy Green of WMM, Bob Jaeck and Captain Greg Stamatelakys of WMHS and the Wisconsin Underwater Archeology Association, and Russ Green and Caitlin Zant of the NOAA Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary, along with other known associates of theirs.

They began the process of removing the artifacts from the front yard for transportation to WMMs storage facility and future conservation and display. Moving the anchor required the use of a cutting torch. I rapidly began freezing to death, so I observed the proceedings from a spot next to the right front wheel of the crane truck, whose running engine blew a blast of hot air onto my shivering frame.

The anchor went first. Jason Klopp said that his father had put it in front of the house about 25 years ago. Butch recovered the anchor from the 1880 wreck of the schooner AMERICA off Two Rivers, Wisconsin. It is about eight feet tall and the scale on the crane truck showed it weighed 3,600 pounds.

After it was cut loose, the crane lowered it onto a custom-made T shaped frame made of recycled steel I beams from a solar farm near Two Rivers. The anchor was secured to the frame and then the crane lifted them together onto a flatbed trailer towed by Brandan Gauthier, who fabricated the artifact mounts in his shop in Two Rivers.

The next to go was the rudder assembly. Jason said it was from the 1868 wreck of the schooner NORTHERNER, which sank south of Port Washington, off the long-gone town of Port Ulao. The NORTHERNER was one shipwreck that always had a special place in Butch’s heart.

It almost killed him.

Jason said that when diving the NORTHERNER once Butch’s bottom timer ceased to function. By the time Butch realized that he had stayed down too long he no longer had enough air to make the proper decompression stops on the way up. Having to choose between drowning and the bends, Butch surfaced only to suffer one of his three hits of the bends.

This one was in his spine, which was made worse by a preexisting spinal injury. Butch was rushed to the same decompression chamber at St. Luke’s that I came to know so well, where he was told that he could either die or become a quadriplegic for the rest of his life. Butch did neither and returned to his passion of diving.

I had always wanted to see the NORTHERNER on the bottom of the lake, but never did. At last I got to see part of it, albeit on dry land. When Kevin Cullen climbed on top of it, he found what he first thought was concrete in the top of the assembly between the tiller and the shaft. It turned out to be compacted sand and gravel from the bottom of the lake, still in place after 154 years.

It should be noted that shipwreck guru Kevin Cullen of WMM believes that the rudder in question is actually from a trading sloop named the BYRON.

The crane lifted the entire rudder assembly onto a flatbed trailer towed by a F350 pickup driven by a longtime scuba diver, Letitia “Tish” Hase, who used to run a dive shop in Port Washington until COVID closed her down.

Kevin noted that the wooden parts of both artifacts were “preserved well”. The wooden anchor stock had been tarred, and the rudder assembly had been treated with “a concoction” that Butch had obtained 40 years earlier from an unknown UW System professor.

The entire Klopp family was present during this procedure. In addition to son Jason and his mother Paula, daughters Nikki, Wendy, and Kim and Kim’s husband watched the proceedings. Nikki could be easily identified. She spent much of the day praying out loud for a quick return to Florida.

Next to go was the six foot wide iron windlass located directly in front of the house. Unfortunately, Butch’s catalog of shipwreck artifacts did not disclose where this came from. Kevin and Cathy estimated that it came from a steam ship of the early 1900s vintage. It too was well preserved. The crane truck lifted it into the bed of Tish’s pickup.

Last to go were two segments of iron anchor chain that Butch had stretched across the front of his yard. These went into Tish’s pickup but where the anchor chain came from is also unknown. The iron capstan visible in the Google Street View photo was not present on December 12.

Which leaves us with the artifact you are all probably wondering about: the cannon from the Spanish galleon. Butch’s back yard contained a number of other bits and pieces of shipwrecks, but right in the middle of the back yard sat a cannon on a trailer. Jason Klopp said that it was the one item in the Klopp Collection that Butch Klopp did not collect. He said that in the 1970s Butch had a friend who was a treasure hunter who had looked for Spanish galleons in the Caribbean in the 1930s. The friend recovered the cannon and gave it to Butch as a gift. The cannon, along with a number of other artifacts, will be retained by the Klopp family.

Well, all good things must come to an end. And so it was with the many careers of the remarkable Butch Klopp. First to go was his police career. Butch was retired on a medical disability against his will in 1982. Butch suffered a serious back injury when he tried to break up a fight between three drunks and they pushed Butch over a railing on edge of the Port Washington harbor. This aggravated a pre-existing on duty back injury.

Then, as mentioned previously, Butch gave up shipwreck diving when the collection of artifacts was made illegal. And finally, after a long struggle with cancer and spinal injuries, and like me, three hits of the bends, Butch went down on the dive which we all must take and from which none of us will return, dying of cancer in 2021.

The Klopp family wanted to donate Butch’s remarkable collection as a memorial to a remarkable man. His wife Paula wanted to display the collection somewhere in Port Washington but there were no facilities that could handle it. After discussing it with Cathy Green of the Wisconsin Maritime Museum, the family developed “a really good feeling” about donating the collection to WMM and they are “excited for the future,” according to Jason.

Jason Klopp said that he hoped that the Klopp family donation would send a message to other pioneering wreck divers of Butch’s era. Jason noted that many of those divers are passing on as well, and what will happen to their collections is unknown. Their relatives may not realize the value of the items that their family diver pulled up and may simply discard them.

In addition, Jason pointed out that many of the divers of that era were bitter when the government outlawed their passion. Many of them put a great deal of time and expense into recovering their artifacts. As they saw it, they bought boats, diving equipment and sonar gear, spent hours and hours researching wrecks, and got the bends and risked their lives diving deep into dark, cold water in an effort to save history from the zebra mussels.

Jason is concerned that they may simply dispose of their collections to keep them out of the hands of the government. He hopes that others may follow the example that the Klopp family made in conserving the Klopp Collection and donate their artifacts to the Wisconsin Maritime Museum or another museum where they can be preserved for future generations to appreciate and to commemorate the pioneer divers who recovered them, like Butch Klopp.

____________________________________

James Heinz is the Wisconsin Marine Historical Society’s acquisitions director. He became interested in maritime history as a kid watching Jacques Cousteau’s adventures on TV. He was a Great Lakes wreck diver until three episodes of the bends forced him to retire from diving. He was a University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee police officer for thirty years. He regularly flies either a Cessna 152 or 172.

Photo on top of page: 1924 Rollin salvaged from the LAKELAND in 1970. Great Lakes Marine Collection of the Milwaukee Public Library and Wisconsin Marine Historical Society.

Other photos:

Others shown in photos: Kevin Cullen, Brandon Gauthier, Cathy Green, Russ Green, Letitia “Tish” Hase, Bob Jaeck, Greg Stamatelakys, Caitlin Zant

Photos by James Heinz unless otherwise noted.